Fish Tales

The Xiphophorus Genetic Stock Center — a top TXST research center — is expanding its study of the genetic interactions underlying human diseases

By Matt Joyce

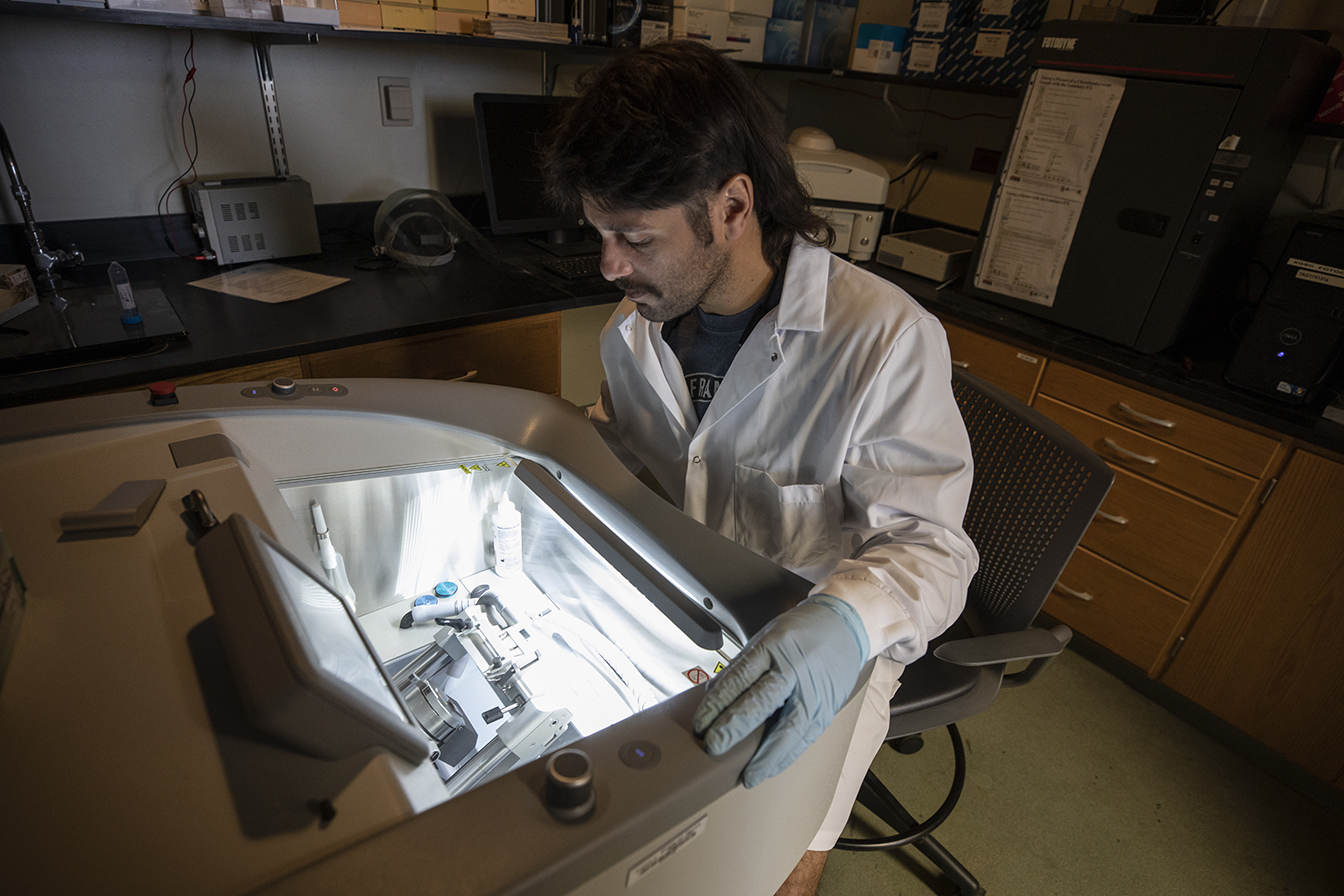

In the heart of Texas State University’s San Marcos Campus, down a nondescript hallway in Centennial Hall, the Xiphophorus Genetic Stock Center greets visitors with an unexpected sight. Here, more than 5,000 little fish dart about in 1,400 tanks stacked in rows across multiple rooms.

The Xiphophorus fish represent a living library of a genus found in Mexico, Guatemala, Belize, and Honduras that help scientists study a range of human diseases. Caretakers at the center, which is known as the XGSC, work daily to clean the tanks, and feed and breed the fish. The center’s researchers study the fishes’ genetics and hybridize them to better understand the molecular origins of diseases such as cancer, diabetes, and obesity — and potential therapies.

“Some of these fish lines have been maintained for more than 100 generations,” said Markita Savage, the operations manager who oversees a fish technician and six students that maintain the tanks. “We have one species that’s extinct in the wild and several others that are endangered.”

The XGSC made its name with pioneering research of Xiphophorus fish and how their biological traits provide clues to human health, particularly cancer research of melanoma. Now, with funding from the National Institutes of Health (NIH), the center is expanding its research to develop new disease models to uncover the genetics behind conditions in organs such as the eyes, gonads, and brain.

The NIH awarded the center a $3 million R24 grant last summer to expand its resources for non-cancer disease research, said Dr. Yuan Lu, associate director of the center. “The R24 grant is building on the success of our cancer research,” he said. “But we want people to know Xiphophorus research is not only for melanoma.”

A time-lapse video shows some of the typical daily activities of the XGSC.

Shepherded by a succession of scientists over the decades, the XGSC got its start at Cornell University in the 1930s. The center later moved to the American Museum of Natural History in New York and the New York Aquarium before moving to the MD Anderson Cancer Center in Smithville, Texas. In the early 1990s, researchers transferred the center to Texas State.

The center has garnered $30 million in NIH funding since its relocation to Texas State, said Dr. Michael Blanda, XGSC director and chief operating officer for TXST’s Division of Research. As a university-level research center with a unique mission, the XGSC is a key part of TXST’s “Run to R1” initiative to achieve Carnegie status as an institution of “very high research activity.”

The center’s research and academic awards “are the foundation for creating new knowledge and provide many students with opportunities to learn about and participate in cutting-edge research to propel their professional and academic careers,” Blanda said. “The XGSC has developed a reputation for housing some of the best genomic resources in the world, and this outreach and training reputation has spread to institutions both within the U.S. and around the globe. This past year alone, the XGSC brought scientists from Stanford University, Germany, and Brazil to work, study, and train at Texas State.”

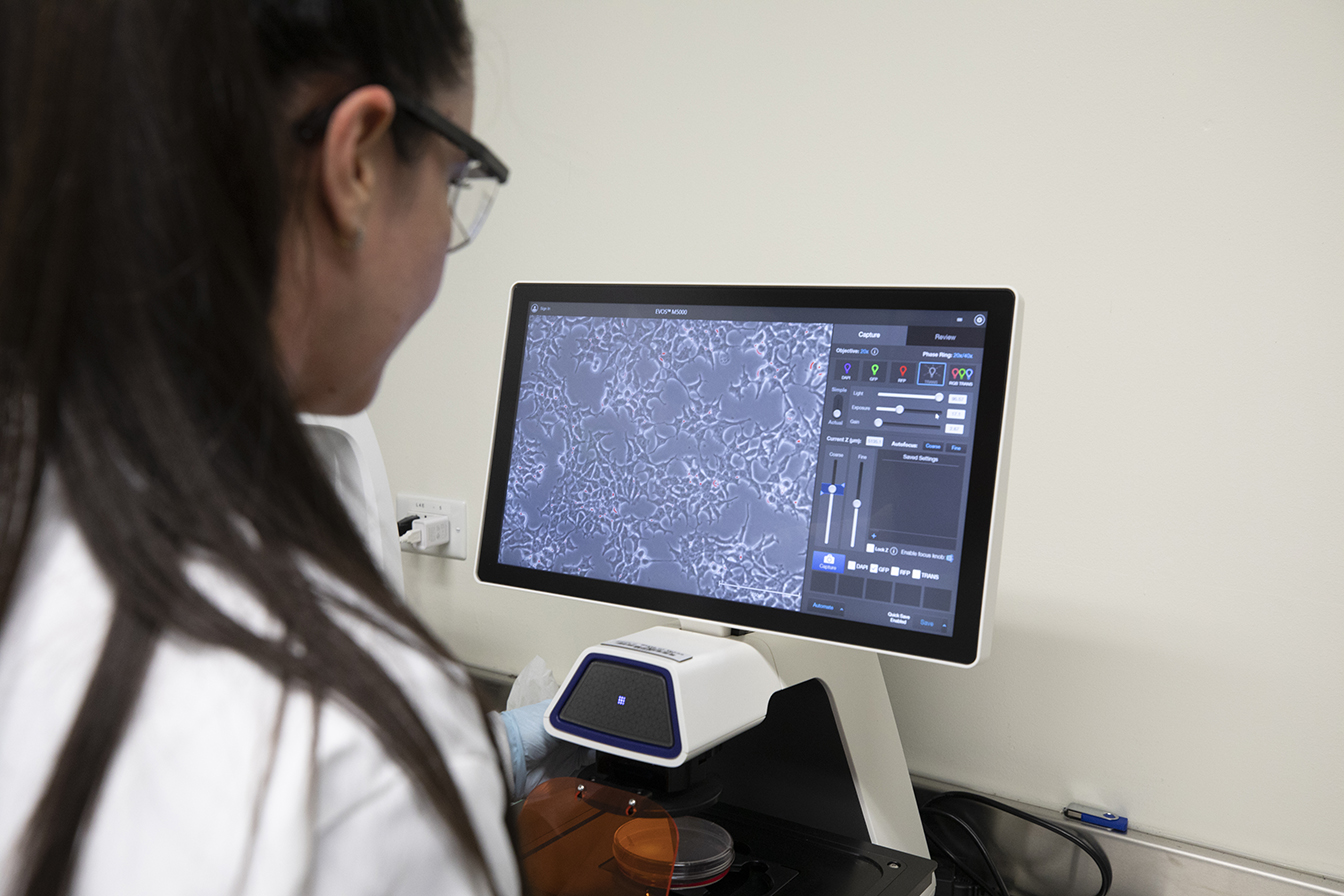

Lu recently co-authored a paper with his stock center colleagues Dr. Manfred Schartl, Dr. Kang Du, William Boswell, and Mikki Boswell laying the groundwork for disease research beyond melanoma. Titled "High resolution genomes of multiple Xiphophorus species provide new insights into microevolution, hybrid incompatibility, and epistasis," the paper was published this summer in the journal Genome Research.

The paper’s goal was to assess microevolutionary processes within Xiphophorus fish to identify molecular events that lead to the divergence of the Xiphophorus species and to reveal genetic incompatibilities underlying human disease, Lu explained.

For people who keep aquariums at home, the Xiphophorus genus is not unfamiliar. They have names like swordtails and platyfish. The genus is useful for research because there are numerous different species; the species have diverse genetic backgrounds; the species can form interspecies hybrids that are fertile; and the genomes for each species have been sequenced. The XGSC maintains over 60 different strains of Xiphophorus fish for specific genetic traits.

“The reason we do the interspecies hybrid is to recreate incompatible genetic interactions that can lead to a disease that is similar to a human condition,” Lu explained. “Since the genomes are sequenced, we can track the allelic [DNA sequence] combination within the hybrid. When you see different phenotypes between two different species, you can track that down to a specific gene.”

By isolating certain genes, TXST researchers have discovered fish traits such as a neck hump that could be related to the genes that cause human obesity and cranial deformation that could be related to Down syndrome. Both findings require more research to determine whether they’re applicable to human conditions, Lu said.

“We know the diseases that are relevant to the hybrids are not only melanoma, but also other type of diseases,” he said. “With the NIH funds, we can conduct the relevant research.”

Dr. Caitlin Gabor, a professor in the Department of Biology, serves as XGSC associate director along with Lu. Part of her focus has been developing internal and external collaborations for the center. She described them as “collaborations from a more ecological perspective but tied to biomedical questions.”

For example, a postdoctoral student from Spain has worked with the center to study how telemores (a part of chromosomes) and oxidative stress indicate the aging process of different species of Xiphophorus fish maintained in the same environment. The center has also worked with TXST's Department of Biology to explore how maternal exposure of live-bearing Xiphophorus fish to aquatic nitrite impacts her in utero offspring after birth.

Collaboration is at the forefront of the center’s Aquatic Models of Human Disease Conference, with the next edition scheduled for October 2024 in San Antonio. The conference brings together top scientists, postdocs, and students from around the world, as well as federal funding agency representatives. “This exposure of not only the XGSC, but of the university at large, is one of the best worldwide scientific outreach opportunities at Texas State,” Blanda noted.

Back at Centennial Hall, Savage said passing students will sometimes stick their heads in the door, surprised by the aquariums. No doubt, the fish are a mesmerizing sight. “Come on in,” she tells visitors. “We’re happy to give tours. I’ve done tours for little bitty preschool kids all the way up through college students.”